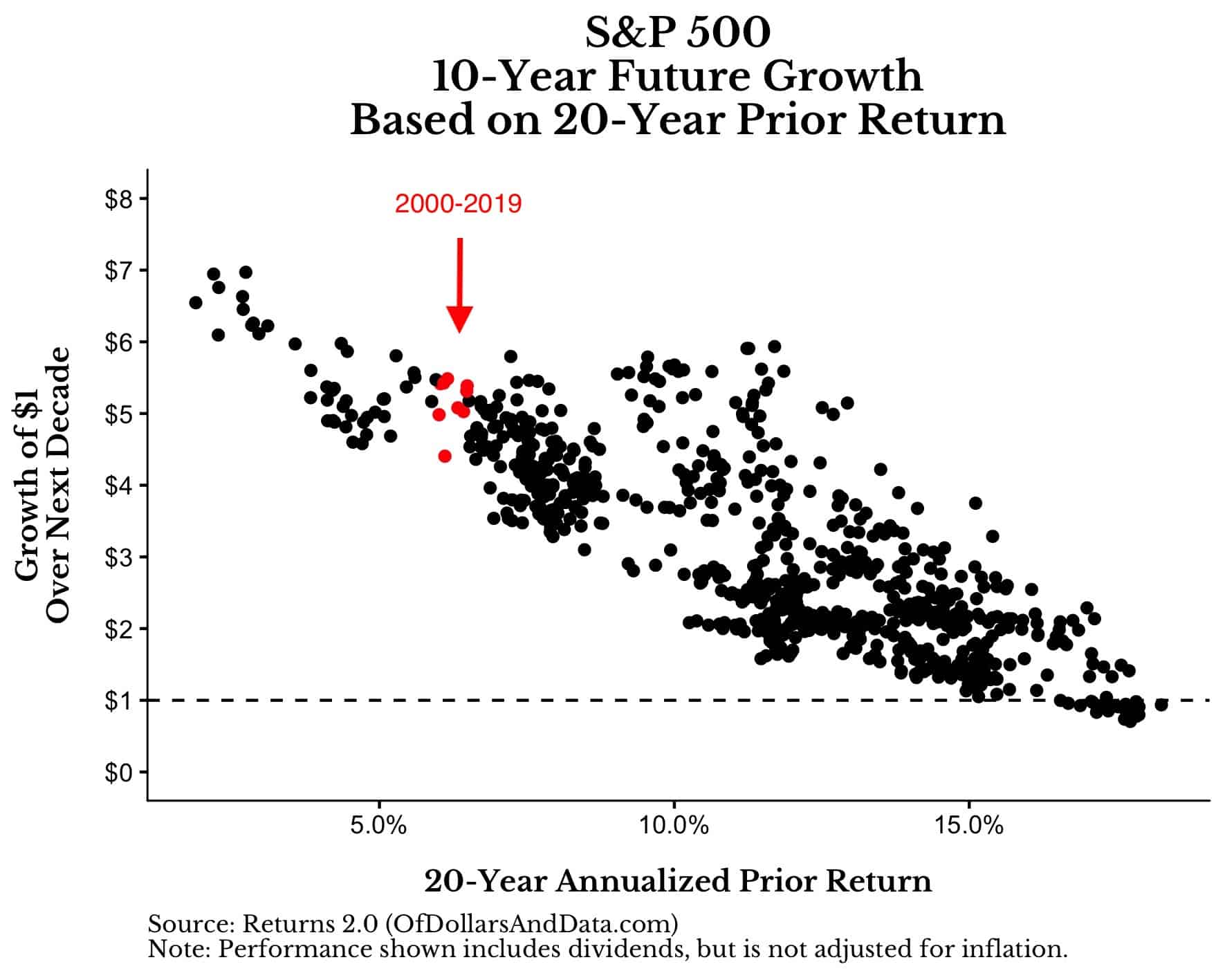

At the beginning of 2020, I argued that the S&P 500 was likely to be 4x higher by 2030. This “prediction” came from a chart that looked at the future 10-year growth in the S&P 500 based on the prior 20-year returns. All I did was calculate the S&P 500’s return over the last 20 years (i.e. from 2000-2019) and then found other periods that had a similar prior 20-year return historically.

To be specific, U.S. stocks had 6% annualized returns (with dividends, but not adjusting for inflation) from 2000-2019, so below I highlighted (in red) historical periods that also had 6% annualized returns over their prior 20 years:

As you can see, when we look at just these historical periods, the S&P 500 was up anywhere from 4x to 5.5x in nominal terms over the next 10 years. This means that, if history were to repeat itself, any dollar invested in the S&P 500 at the beginning of 2020 would be worth between $4-$5.50 (in nominal terms) by 2030.

At the time when I posted this, the S&P 500 index was around 3,200. Therefore, for my prediction to come true, it would need to be around 12,000 by 2030 (Note: this figure isn’t exact because dividend and dividend reinvestment contribute to your overall return, but are not included in the index level).

Well, guess what? We are half way to 2030 and the S&P 500 is at around 5,975 (or a little less than halfway to its 12,000 target). Yes, I know how crazy this prediction sounds. It sounded crazy when I wrote it in 2020 and it seems even crazier today. But, if we look under the hood, this “prediction” isn’t as ridiculous as it initially seemed.

Why an S&P Target of 12,000 in 2030 Isn’t Unreasonable

The reason why a S&P 500 price target of 12,000 in 2030 isn’t as far-fetched as it sounds is because this is a nominal value, not a real one. When I did my original analysis back in early 2020, I included dividend and their reinvestment in my returns, but I did not adjust for inflation. Now that we’ve experienced a period of high inflation (hello 2022), you can understand why this was an oversight on my part. Because, after adjusting for inflation, an index value of 12,000 in 2030 won’t actually mean a doubling in purchasing power from today.

To have a better understanding of this, let’s just look at how the S&P 500 performed over the last 5 years (since early 2020). If you use my S&P 500 historical calculator, you will see that the S&P is up 98% in total return but only 62% when adjusted for inflation over this time period. So while on paper the S&P 500 doubled in 5 years, after inflation it’s not as remarkable. This was the primary issue with my 2020 blog post and why, psychologically, a 4x return in the S&P 500 over a decade sounded crazier than it actually was.

So what does the data look like if we use inflation-adjusted returns instead? Below I have plotted the same chart as above, but this time I used the Shiller data, which adjusts for inflation. Note that I subset this data to match the original analysis (from 1926 onward) and, once again, highlighted (in red) all periods that had similar prior 20-year real returns as 2000-2019 (i.e. 3.5%-4.0% annually after inflation):

After adjusting for inflation, the S&P 500’s returns over the next 10 years aren’t as extravagant as my original analysis (which was in nominal dollars) suggested. Though there are still some similar periods with 4x real growth over the next 10 years, there are far more with only 1.75x-2.75x growth.

As a result, this is the “prediction” I should’ve gone with in 2020—1.75x-2.75x real growth, not 4x nominal growth. Though they represent the same thing, mentally the 1.75x-2.75x real growth seems more realistic.

And while the relationship between prior and future returns for U.S. stocks isn’t guaranteed to hold in the future, it has been surprisingly strong historically. For example, from January 1980 to December 1999, the S&P 500 had 13% annualized real returns, which suggests very low real growth over the next 10 years (i.e. from 2000-2009):

And guess what? Just like the chart would’ve predicted, from January 2000 to December 2009, $1 invested in the S&P 500 would become $0.73 in real terms, for an inflation-adjusted loss of 3.16% annually over 10 years.

And no, this isn’t just the 2000-2010 data biasing the data. If we could go back to December 1999 and recreate this chart (i.e. exclude the data from 2000 onward), here is what it would look like:

In other words, in December 1999, this historical data was suggesting poor future returns, and, over the next decade, U.S. stocks had poor returns.

Of course, there are many arguments to be made about why this relationship may not hold in the future. For example, some people will argue that this data isn’t useful because it contains too many overlapping periods. After all the period of 1926-1945 is very similar to the period of 1927-1946, so why count them as separate observations. This critique isn’t wrong, but what other choice do I have? If I had to use non-overlapping 20-year periods, I wouldn’t even have 5 data points to rely on (starting in 1926).

Either way, I bet you are still wondering: what is this data series predicting for the next 10 years as of today? Well, I have good news and I have bad news.

The bad news is that things don’t look as bullish as they did in 2020. But, the good news is that U.S. stock returns over the next decade still look decent. Based on the periods in history where U.S. stocks returned 6.75%-7.75% (after inflation) for the prior 20 years (as they did from 2005-2024), here is what their growth over the next 10 years looked like:

While there are some periods with low growth (~25% total return over the next decade), there are also quite a few periods that saw a 100% real return (or greater) within the next 10 years!

Though this data isn’t perfect, it’s more predictive than I would’ve thought. For example, if you run a simple linear regression where the y variable is future 10-year returns and the x variable is the prior 20-year returns, the R^2 of this regression is 0.55. This means that 55% of the variance in 10-year future stock returns can be explained by the prior 20-year returns:

The funniest thing about this is that it’s not even the best performing simple linear regression. If I re-run the regression with the prior 25-year returns (instead of the prior 20 year return) the R^2 increases to 0.61! That’s an incredible amount of explanatory power for a single variable. Of course, there are much better predictors of future stock returns out there (e.g. Fama-French’s factor models), but my point remains.

Whatever you decide to believe, it seems very possible that this isn’t a complete statistical fluke. What seems more likely is that the U.S. has had a relative consistent business cycle over the last 100 years. However, whether this consistency will continue in the future remains to be seen.

Either way, I’m short-term neutral, but medium-to-long-term bullish going into 2025. Of course, U.S. stocks don’t seem cheap at these levels. But, if history is any guide, then they might have more room to run than you think. Then again, I can only show you the data. You’re the one that has to decide what to do with it.

Wishing you an incredible 2025 and thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 432. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data