You made it. After decades of hard work and saving, you are finally ready to retire. Though you are mentally prepared to enter your golden years, a new challenge lies ahead—how do you convert your accumulated savings into a sustainable income stream that will last for the rest of your life?

While the idea is simple—just withdraw what you need—the execution isn’t. Factors such as market volatility, inflation, and healthcare costs will all play a critical role in determining your future retirement withdrawals.

In this post, we’ll explore various withdrawal strategies in retirement and help you understand which approach might be best for your particular situation. With that being said, let’s start with the most popular retirement withdrawal strategy of all, the 4% Rule.

The 4% Rule (Safe Withdrawal Rates)

In 1994 William Bengen published research in the Journal of Financial Planning that would change how we thought about retirement forever. Titled Determining Withdrawal Rates Using Historical Data, Bengen ran a historical analysis on how much money you could withdraw over the course of your retirement and analyzed what would happen to you as a result.

Bengen found that, for a 50/50 stock/bond portfolio, the most you could withdraw without running out of money over 30 years was 4% per year (with annual inflation adjustments). As the paper states:

Assuming a minimum requirement of 30 years of portfolio longevity, a first-year withdrawal of 4 percent, followed by inflation-adjusted withdrawals in subsequent years, should be safe.

So, if you had a $1 million portfolio to start retirement, in year 1 you would withdraw $40,000 [4% of $1 million]. If inflation in Year 1 was 3%, then in Year 2 you would withdraw $41,200 [$40,000 * 1.03], or 3% more than in Year 1. And so forth.

This simple calculation (Annual Spending in Year 1 = 4% of portfolio value) allowed retirees to solve a very complex problem without needing to do complex math. As a result, the 4% Rule was born and the name stuck.

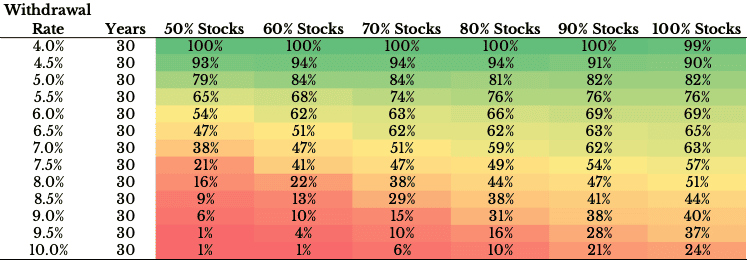

Technically, the 4% Rule is a safe withdrawal rate (SWR) strategy. This strategy is a great starting point for a conversation about retirement withdrawals for two reasons. First, it’s easy to understand. Most people get it right away. Second, the SWR strategy (especially the 4% Rule) has worked very well historically. Below is a heat map comparing various stock/bond portfolios and their survival probabilities across every 30-year retirement from 1926-2022 (for various withdrawal rates):

As you can see, only a withdrawal rate of 4% had a 100% survival probability across basically every portfolio allocation. This is how the 4% Rule became the popular safe withdrawal rate.

Another reason the 4% Rule became popular is because it takes into account sequence of return risk. As I’ve discussed previously, sequence of return risk is the idea that the order of your investment returns matters for whether you run out of money in retirement.

The reason is because you are withdrawing money from your portfolio over time. So, if you withdraw during a market crash, you will have less money invested during any subsequent recovery. And if you keep withdrawing with less money invested, it is a downward spiral until you run out.

The 4% Rule reduces such risk because it’s conservative. Historically, no matter what sequence of returns you got, you would’ve survived by only withdrawing 4% in any given year.

Does this mean that the 4% Rule is right for you? Not necessarily, but such historical simulations can be helpful when trying to decide your asset allocation and withdrawal rate in retirement.

While I love the 4% Rule for its elegance and simplicity, its quite inflexible and requires a significant retirement balance to be effective. For those that have less money saved or are willing to be open-minded about how they spend money in retirement, there is a better way. For this, we turn to the Flexible Spending strategy.

Flexible Spending Strategy

The Flexible Spending strategy requires that you adjust your retirement withdrawals based on market conditions. To do this, first you have to categorize your spending into two categories: required and discretionary. Your required spending is the spending that you have to do every year. It is fixed and it adjusts annually with inflation (just like with the 4% Rule).

However, your discretionary spending includes all the things in life that are nice to have, but not necessary in retirement. This could include nice vacations, going out to eat, or expensive concert tickets. Whatever feels discretionary to you is. More importantly, this spending does not change with inflation. It is a fixed amount that is discretionary for your entire retirement.

Once you have your required and discretionary spending set, then you follow rules on how much to spend based on market conditions. As I stated in this post:

On December 31 of each year you check to see how far the S&P 500 is away from its all-time highs. Based on that number, your discretionary spending falls into one of three possible conditions:

- Normal market: If the S&P 500 is less than 10% away from its highs, you spend all of your discretionary spending in the next year.

- Correction: If the S&P 500 is more than 10% away from its highs but less than 20% away from its highs, you spend half of your discretionary spending in the next year.

- Bear market: If the S&P 500 is more than 20% away from its highs, you spend none of your discretionary spending in the next year.

The downside to this strategy is that, in some years, you have to cut back on your lifestyle because you have no discretionary spending. However, the upside is that you can spend more in retirement in the other years. How much more?

Historically, you could’ve survived with a 5.5% withdrawal rate rather than a 4% withdrawal rate by using the Flexible Spending Strategy when 50% of your spending is discretionary.

Note that you don’t get to spend more total money over your retirement when using this strategy (there is no free lunch), but you do get to spend a bit more in most years.

If you’d rather not have discretionary and required spending categories, but you still want to adjust your spending based on market conditions, then the Guardrail strategy might be right for you.

The Guardrail Strategy

The Guardrail strategy is a dynamic approach to retirement withdrawals where your spending adjusts based upon predetermined “guardrails” or threshold portfolio values. For example, if your portfolio value exceeds the upper guardrail, you are allowed to increase future withdrawals. However, if your portfolio value drops below the lower guardrail, you have to decrease future withdrawals.

The amount you increase or decrease your withdrawals is up to you. For example, let’s say you start retirement with a $1 million portfolio and you decide to withdraw $40,000 a year (4%) and you don’t adjust it annually for inflation. In addition, you set the following guardrails on your portfolio:

- Upper Guardrail = $1,333,333

- In this scenario $40,000 represents 3% of your portfolio value.

- Lower Guardrail =$800,000

- In this scenario $40,000 represents 5% of your portfolio value.

So, you start withdrawing $40,000 a year and keep doing so unless your portfolio value exceeds one of your guardrails. If your portfolio goes above $1,333,333, then you could increase your spending to $53,333 (4% of $1,333,333) and reset your guardrails. However, if your portfolio value fell to $800,000, you’d have to decrease your spending to $32,000 a year (4% of $800,000) and reset your guardrails (downward) as well.

This is just one way to use the guardrail strategy. You could also just increase (or decrease) your spending by a predetermined amount when you hit a guardrail. Using our prior example, if your portfolio hit $1,333,333, you could increase your spending to $50,000 a year (instead of $53,333). On the other hand, if it dropped to $800,000, you could decrease your annual spending to $30,000 a year (instead of $32,000). There is no right answer here, just the one you feel comfortable with.

The Guardrail strategy provides flexibility and responsiveness to market conditions, potentially extending the longevity of your retirement funds. It’s particularly useful for managing the psychological discomfort associated with fixed withdrawals by adapting to real-time financial realities. In doing so, you are also less likely to run out of money since you withdraw less as your portfolio declines in value.

The downside of the guardrail strategy is that you may be forced to spend less money in the future. If you have a lot of discretionary spending, this shouldn’t be a problem. However, if most of your retirement expenses are required, spending less may be difficult and you may deplete your portfolio as a result.

If you don’t like the idea of adjusting your retirement spending based on market conditions, then the bucket strategy is a great alternative that also provides peace of mind.

The Bucket Strategy

The Bucket strategy works by bucketing your spending into short-term, medium-term, and long-term categories and then investing each bucket accordingly. For example, money needed to pay for food and other immediate expenses could be invested in short-term Treasury bills or cash while those expenditures that won’t happen until later (i.e. grandchildren, etc.) can be invested in stocks and other risk assets.

For example, someone with a $1 million portfolio using a Bucket strategy might have their money invested in the following way:

- Short-term bucket: $120,000 in a high-yield savings account or short-term Treasury bills. This covers your living expenses for the first 3 years.

- Medium-term bucket: $400,000 in a balanced mix of stocks and bonds. This portion is for years 4-10 of your retirement, offering a balance between growth and safety.

- Long-term bucket: The remaining $480,000 in diversified stock funds or ETFs, aiming for growth over the long term.

The idea behind the Bucket strategy is to match your investment strategy with the actual liabilities you expect in retirement. This can provide you with more peace of mind than having all of your money in a single account (or bucket).

Though your overall portfolio allocation may be the same between a Bucket strategy and a safe withdrawal rate (SWR) strategy like the 4% Rule, there is an additional layer of psychological comfort here. By breaking your money into different buckets, you may feel more at ease with your spending regardless of what the market does. After all, what matters more in retirement than peace of mind?

While the Bucket strategy is one way to feel comfortable in retirement, there is another, even simpler strategy that most retirees tend to use in their final decades.

What Most Retirees Actually Do (Never Spend the Principal)

Despite the many different approaches to spending money in retirement, the data suggests that there is a far simpler strategy that most retirees tend to follow—never spend the principal. In other words, spend up to your income in retirement and not a penny more. For example, if a retiree had $1,500 a month in social security income and another $1,500 a month in investment income from their portfolio, they would be able to spend up to $3,000 a month (or $36,000 a year).

This strategy is arguably the simplest and most conservative out of all the withdrawal strategies mentioned thus far. It’s simple because money going out matches money coming in. And it’s conservative because the principal balance is never reduced, so there is always a surplus to rely on, if necessary.

But how many retirees “never spend the principal”? The data suggests that it’s the vast majority. As I wrote in Just Keep Buying:

As the Investments & Wealth Institute reported, “Across all wealth levels, 58 percent of retirees withdraw less than their investments earn, 26 percent withdraw up to the amount the portfolio earns, and 14 percent are drawing down principal.”

According to this report, only 1 in 7 retirees (14%) end up touching their principal during retirement. The rest live on their income (or less than their income) in their golden years.

When I first read this statistic I couldn’t believe it. The financial industry spends so much time and energy doing all this complicated math and planning on how to spend money in retirement and, yet, the vast majority of retirees ignore it.

This made me realize that most people rely on simple rules and heuristics when making financial decisions. And when it comes to spending money in retirement, nothing is simpler than “Never Touch the Principal.”

Now that we’ve reviewed how most retirees actually spend their money in retirement, let’s wrap things up by discussing why the ideal retirement strategy is in the eye of the beholder.

One Approach to Rule Them All?

There are many ways to spend your money in retirement. While choosing the right option can be overwhelming, I actually think having so many options is a good thing. Because you can test them out and see what works for you.

If seeing your portfolio value decline bothers you, then you might choose the Never Spend the Principal approach. If you don’t like the inflexibility of the 4% Rule, then maybe a Flexible Spending strategy or Guardrail will work better. Lastly, maybe spending isn’t the issue but how you frame it. For this, the Bucket approach might be well suited for your taste.

Ultimately, there is no one approach to rule them all. Every strategy has its pros and cons. The key is experimenting with different approaches and seeing how you feel. You may not have the right answer now, but you will find the answer in time.

I will admit that I have no clue how I am going to spend my money in retirement. After all, I’m still 25 years or so away from it. But what I do know is that I will figure it out when I get there. We all do.

If you’re interested in learning more about retirement withdrawal strategies (or retirement in general), I highly recommend How to Retire by Christine Benz. It’s the most comprehensive retirement book I’ve ever read.

Happy investing and thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 453. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data

Leave a Reply